Could a trade deal lift the US’ longstanding ban on crude oil exports? Europe thinks so.

Washington Post | 8 July 2014

Could a trade deal lift the U.S.’ longstanding ban on crude oil exports? Europe thinks so.

By Lydia DePillis

The European Union is pressing the United States to lift its longstanding ban on crude oil exports through a sweeping trade and investment deal, according to a secret document from the negotiations.

It’s not entirely surprising. The EU has made its desire for the right to import U.S. oil known since the U.S. started producing large amounts of it in the mid-2000s. It signaled again at the outset of trade negotiations, and its intentions have become even more clear since.

This time, though, the EU is adding another argument: Instability on its Eastern flankthreatens to cut off the supply of oil and natural gas from Russia. "The current crisis in Ukraine confirms the delicate situation faced by the EU with regard to energy dependence," reads the document, which is dated May 27.

The leak comes in advance of another round of discussions on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, which kicked off last fall and is expected to encompass $4.7 trillion in trade between the U.S. and the European Union when it’s finished (here’s an explainer on the deal). That won’t happen for several years — if ever — but knowledge of the E.U.’s position has inflamed the already-hot debate over whether to allow the U.S.’ newfound bounty of crude oil to be exported overseas.

Particularly irksome to environmentalists is the EU’s request that the U.S. make a "legally binding commitment" to export its oil and gas, which U.S. negotiators have so far resisted, according to the correspondence. (The U.S. Trade Representative declined to comment on a leaked document, except to say that it’s too early to characterize its position on any matter).

"We find it particularly outrageous that a trade agreement negotiated behind closed doors is being used as a means to secure automatic access to both crude oil and natural gas," said Ilana Solomon, director of the responsible trade program at the Sierra Club. "By lifting the ban, you’re creating a whole new market for the oil industry to export to, and windfall profits for oil companies, which means more money to frack more, to produce more, to burn more."

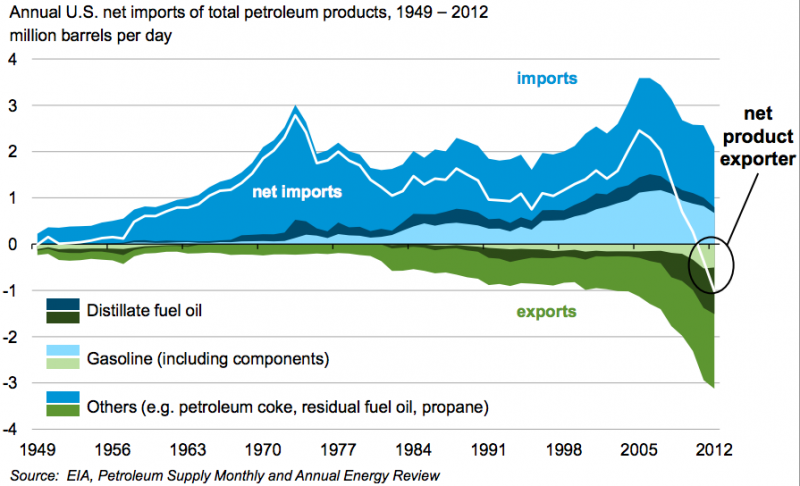

The issues of natural gas and oil are closely related, but distinct. The U.S. already allows more natural gas to be exported, especially to countries with which it already has trade agreements. Crude oil is the one thing that’s remained at essentially zero exports since 1975, when Congress banned its sale to preserve access if something like the Arab oil embargo were to occur again.

Now, Europe feels that it’s in a similar situation. Although fossil fuel use has been declining, it’s still not ready to transition to renewable energy sources, and remains heavily dependent on imported oil — 39 percent of which comes from the tumultuous Middle East and Africa, and 42 percent from the former Soviet Union. The U.S. is a huge potential source of supply, having recently overtaken Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest producer of oil and gas. Also, while U.S. refiners had retrofitted their operations to process heavier oil imported from the Canadian tar sands before the fracking boom delivered a flood of new supply, Europe’s refineries are well-equipped to handle it.

But who, exactly, is pushing for more U.S. crude behind the EU’s unified veneer? The Council of the European Union did not respond to a request for comment. Industry watchers, though, point out that Germany still depends on oil as its primary source of energy — as opposed to, say, France, which gets 75 percent of its power from nuclear plants. Half of Germany’s oil comes from former Soviet Union nations, and some of it used to come from Libya before rebels shut down export terminals there (the supply only just started flowing again). Germany is very influential within the EU, and may have pushed the trading bloc to raise its voice on measures that would help it diversify its supply over the long term; the letter itself admits that there’s no way to stabilize Ukraine with U.S. oil imports soon enough to make a difference.

Plus, Europe’s protest isn’t just about oil. It’s also about messaging.

The first message is external. The letter emphasizes that both parties give lip service to the idea of free trade, and America lifting its own giant violation of that principle — the crude oil export ban — would demonstrate to countries like China that the two economic superpowers are serious about tearing down barriers.

"Combatting resource nationalism, together vis-à-vis third countries, while at the same time allowing for export restrictions to exist between us sends the wrong message to our partners," the letter reads, "and offers some of these resource-rich countries a great opportunity to interpret trade rules in a way which is detrimental to our economies."

The second message, though, is internal: Securing additional energy supplies may help the EU negotiators to sell the agreement to their member states, especially when they might also have to give up some of their protectionist sacred cows, like the agricultural subsidies that have propped up European farmers for decades.

"The Europeans really want to set a precedent, to make a point, that they want free trade and a more liquid market," says Iana Dreyer, who edits the EU trade analysis service Borderlex, where she wrote about a previous leak on the treaty’s energy chapter. "After the oil shock in the 1970s, energy has been so securitized, that the mindset has really changed — now we need a big flexible global market so that nobody can control it."

For its part, the White House has made some moves in recent weeks to free up some subcategories of oil for export, which excited the industry and alarmed environmentalists. And in its letter, the EU expresses confidence that automatically granting export licenses to treaty parties would "not require that the U.S. amend its existing legislation on oil and gas."

It’s unclear how that would happen. Senator Ed Markey (D.-Mass) — who thinks Ukraine should kick its Russian fossil fuel habit through better energy efficiency — has outlined the legal reasons why the White House couldn’t just lift the ban outright through executive action.

Meanwhile, however, the ban itself may be illegal under international trade law. Although no one has ever challenged the U.S. at the World Trade Organization, the American Petroleum Institute — composed of oil majors like Exxon, ConocoPhillips, and BP — intimated late last year that it might do so if the restriction isn’t lifted through other means. And while the U.S. and European governments may not be on the same page on this issue, very large corporate interests on both sides of the pond see it as a top priority.

"Because U.S. and European companies, including energy companies, have invested heavily on both sides of the Atlantic, U.S. and EU negotiators are essentially representing the same company interests," the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s vice president for Europe Peter Chase told Bloomberg. That legal challenge has a non-zero chance of success, says Jim Bacchus, a former chair of the WTO’s appellate body who argued for the National Association of Manufacturers that natural gas export restrictions would run afoul of international trade rules as well.

"Generally speaking, WTO rules prohibit restrictions on exports of any kind, unless they take the form of taxes," Bacchus says. "There has always been this notion that somehow energy products are not products that follow the scope of the WTO treaty. There’s no legal basis for that view."

If the ban stayed in place, however, there’s no guarantee the oil would stay in the ground, as environmentalists would prefer. Rather, U.S. refineries would likely just reconfigure themselves again to process the stuff, and import less heavy oil from Canada. That’s already started, and will likely move even faster if it becomes apparent that the U.S. isn’t going to do what Europe wants.

Overall, the effects of lifting or weakening the ban might not be as large as either proponents or opponents say — especially compared to measures like fuel efficiency standards, which have already driven down demand on both sides of the Atlantic.

"The only groups that seem to believe that lifting the oil export ban will have revolutionary impacts are industry advocates and environmental groups," says Michael Levi, an energy policy expert at the Center on Foreign Relations. "My instinct is that they’re both exaggerating things for different reasons."

Read the document here: