Politics of investment treaty arbitration

SSRN | 20 April 2017

Politics of investment treaty arbitration

by Lauge N. Skovgaard Poulsen

On April 30th 2015, 4.30pm, the London offices of King & Spalding were the target of a staged ‘exorcism’ of corporate power conducted by a group of NGO activists led by Reverend Billy. The Reverend and his followers asked the firm and its lawyers to repent for their cardinal sin: engaging in investment treaty arbitration. Although perhaps the most entertaining, this was but one of a growing number of protests against investment treaty arbitration in Western capitals in recent years.

Until the late 1990s, investment treaty arbitration was an obscure and little used corner of international economic law. That has changed drastically in recent years. Based on more than 3,000 investment protection treaties – most of which are bilateral – foreign investors have increasingly resorted to investment treaty arbitration when resolving disputes with host states. By 2017, more than 700 claims had been brought against more than 100 countries, and the vast majority has been filed in the preceding decade. Claims have been in a large number of sectors and covered a very wide range of public policies. Some claims are about outright expropriation, but typically the broad and vaguely drafted treaties have been used to seek compensation for less intrusive forms of government behavior that would often be subject to broad judicial deference in domestic courts. Most claims have been against developing countries, but also developed countries have been respondents – particularly in recent years. Investors have won or settled more than half of all known claims, including some claims against states with advanced legal systems and property right protections. Awards have occasionally been substantial, with several exceeding billions of dollars.

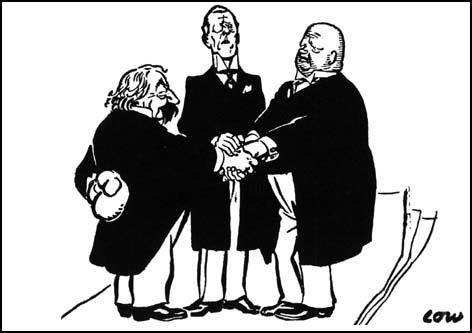

The regulatory reach and financial implications of investment treaty arbitration has made it one of the most potent areas of international dispute settlement. Unsurprisingly, it has also become highly controversial. A leading arbitrator has lamented that, ‘the more [people] find out what we do and what we say, and how we say it, the more appalled they are.’ This includes not just opponents of globalization – like Reverend Billy - but also supporters of international trade and investment. And apart from civil society groups mobilizing against the regime, officials and politicians in some government offices have also begun to question the legitimacy of using a small clique of international arbitrators - typically commercial lawyers - to settle public law disputes.

The chapter will discuss the politics of investment treaty arbitration. Politics is understood very broadly for the purpose of the chapter, encompassing the domestic and international political drivers, effects, and justifications of investment treaty arbitration as well as the political reactions to the regime by relevant stakeholders. The chapter starts with focusing on two core political justifications for investment treaty arbitration.8 The first relates to home state politics and diplomacy: the ability of investment treaty arbitration to de-politicize investor-state disputes. The second justification relates to host state politics and institutions: the ability of investment treaty arbitration to convince certain types of foreign investors to commit capital into certain types of host states. On this basis, the chapter will discuss the politics of investment treaty arbitration in recent years, particularly surrounding the unintended consequences of the investment treaty regime as well as the controversy surrounding investment arbitrators themselves.

Read more (pdf)