The grapes of wrath

Washington Post Magazine | 26 December 2014

The grapes of wrath

The Champagne Bureau’s fruitless (so far) efforts to get truthful labeling for its product is reason enough to drink.

By Jason Wilson

“The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their proper name.” — Confucius

A few months ago, on a sunny Philadelphia afternoon, I joined a dozen people in the private back dining room of a high-end restaurant called Fork, where we’d all been invited to help solve one of the world’s problems. As we listened to the call to action that would undo this injustice, we nibbled at lovely smoked trout caviar served on buckwheat toasts, lamb carpaccio, wild bass tartare served on lettuce leaves, lobster tartine and fancy gourmet pretzel bites. Five different bottles of Champagne chilled on ice.

Think for a moment about all the problems facing the world — problems that involve, at the very least, public service announcements or street riots or hazmat suits or military intervention or vast sums of money or all of the above. The problem broached before the private dining room at Fork was definitely not one of those. In fact, the problem before us seemed to be one of the easier global issues to solve. It basically involved calling things by their proper names.

This gathering happened to be a Champagne education seminar, sponsored by the Champagne Bureau, a little-known lobbying organization based in Washington whose purpose is to convince and educate Americans that “Champagne” should refer only to sparkling wine from Champagne, France. The Champagne Bureau is the organization that raises a ruckus when, say, the White House serves a California sparkling wine for the inauguration and improperly calls it “champagne” on the menu (which happened in 2013).

My fellow attendees were all local restaurant industry types: sommeliers, managers, chefs, culinary educators, bloggers. At each of our seats was a survey. The first question: “Before attending this event, were you aware that Champagne only came from Champagne, France? Please check one. Yes No.”

With empty flutes in front of us, we anxiously awaited the bottles of Champagne to be uncorked. But first there was a PowerPoint presentation by local Champagne Bureau “ambassador” Brian Freedman. “This will be the hardest part of the afternoon,” joked Freedman, a restaurant critic, wine educator and editor of Drink Me Magazine. “You’ll have to muscle through 10 to 12 minutes without any Champagne in the glass.”

Freedman’s PowerPoint covered the Champagne region’s dual oceanic and continental climate, its limestone subsoils, and its gently rolling hills — its terroir, to use the French term used in wine circles. He talked about the region’s grape varieties and degrees of ripeness and yields per hectare. He covered second fermentation and yeast and sugar levels. He explained that, in Champagne, there are 15,000 growers, more than 300 Champagne houses, and 70 cooperatives, and “all of them have to agree on everything, all the rules.” To which he joked: “It’s a very un-American process.”

As he spoke, one message banged like a gong. “Champagne is a place,” Freedman said. “Champagne only comes from Champagne.” One slide showed a map of the world, with text that read, “The Champagne name is protected in 117 countries. The U.S. is among very few countries that allow the Champagne name to be used on wine not from Champagne, France.”

He finally opened the bubbly and began pouring.

Freedman asked if we knew the story of Dom Perignon, the 17th-century French monk who, according to legend, invented sparkling wine by a beautiful accident, and called to his fellow monks, “Come quickly! I am drinking the stars.”

“It’s a great story,” Freedman said. “A lie, but a great story.”

Near the end of the presentation, the fellow in the suit sitting next to me stood and introduced himself as Sam Heitner, director of the Champagne Bureau. He thanked everyone for coming. “Just do me a favor,” Heitner said. “On your wine lists, please separate the Champagne from the other sparkling wines.”

The sommeliers and restaurant managers and wine educators at the table stared at Heitner as if to say, “Who do you think we are? We know the difference.”

Heitner delivered his pitch on the problem, as he has many times before. “Look,” he said, “in this room, we all talk the wine lingo. But at the end of the day, 45 percent of the sparkling wine sold in the United States is mislabeled.”

When I met Heitner for lunch, we ordered Champagne, of course, in this case a Blanc de Blancs from a grower-producer named Jacques Lassaigne. Our server opened the bottle, smiled and asked, “Can I join you? I’m so jealous. What are you celebrating?” She seemed disappointed to learn that ours was only a working lunch.

Heitner has been representing the Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne (the bureau is the U.S. arm of the trade group for Champagne’s growers and winemakers) for more than a decade. “I started doing this when Jacques Chirac and George W. Bush were at each others’ throats,” he said. “I’m an American representing Champagne. I speak with an American voice on this issue.”

But he has also been called “The Sheriff of Champagne” and takes aim at mass-market American wineries that mislabel their sparkling wine as “California Champagne”: André (owned by E. & J. Gallo), Korbel and Barefoot Bubbly, some of the biggest-selling wines in the nation. These brands exploit a loophole in U.S. law that allows them to use “semi-generic” names on labels, as long as the label was granted before 2006, when the U.S. government negotiated a trade agreement with the European Union. “They have what amounts to a grandfather’s clause,” says Tom Hogue, spokesperson for the Alcohol Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau.

This labeling issue affects not only Champagne — there are 16 “semi-generic” terms permitted. There’s also cooking “sherry” sold in supermarkets that’s not from Spain. There’s California “port” that’s not from Portugal. There’s California “Chablis” and Gallo’s “Hearty Burgundy” that are not from Burgundy. In Europe, all of these geographic place names are protected by law, and mislabeling is prohibited. Here, there has been little political will — outside of the Champagne Bureau’s efforts — to close the loophole.

The impact of mislabeling on Champagne, however, is greater than on the others. The average person isn’t often seeking out port or sherry. But everyone — just like our server — knows that “champagne” (whether it’s actually Champagne or not) is the wine of celebrations. Nearly everyone who attends a wedding, an anniversary or a retirement party, or celebrates a victory in business or sports, reaches for something bubbly. “California Champagne” is the cheapest way for caterers and event planners to meet the public’s misguided request for “champagne.”

“People go to weddings all the time and are served what they think is Champagne,” Heitner says. “If that person says, ‘This is terrible. Champagne is overrated. I will never drink Champagne again.’ Well, that is incredibly damaging.”

As someone who writes about wine and spirits, I’ve always been baffled that our government allows companies to slap the word “Champagne” on a $6 bottle of plonk. Americans are comfortable enough with geographic designations on other agricultural or food products: Vidalia onions, Jersey tomatoes, Washington state apples. Wine is an agricultural product. Our laws protect our own geographic place names, such as Napa Valley wines. In 2012, the Champagne Bureau ran an ad campaign that asked, tongue-in-cheek, questions such as: “Maine Lobster from Kansas? Of course not. Champagne only comes from Champagne, France.”

And there are excellent sparkling wines made in the United States — and almost all of these are correctly labeled as, for example, “California sparkling wine.” It’s only the lousy stuff that’s labeled “California Champagne.”

Why do American consumers fall for this nonsense, I asked Heitner. If Heitner had a theory, he wouldn’t share it with me. So I will share my own: When it comes to wine, people feel intimidated, and a lot of consumers think real Champagne is overpriced (conventional wisdom is you don’t really want to drink a Champagne under 40 bucks). Many Americans also still cling to negative feelings about the French (freedom fries, anyone?). So although the American public can certainly understand that Champagne comes from France, they’re not going to be particularly sympathetic to complaints from the French — particularly a French trade group who represents luxury wines that sell for premium prices. For a certain segment of Americans, admitting that Champagne comes only from Champagne is possibly admitting that they will never actually drink Champagne.

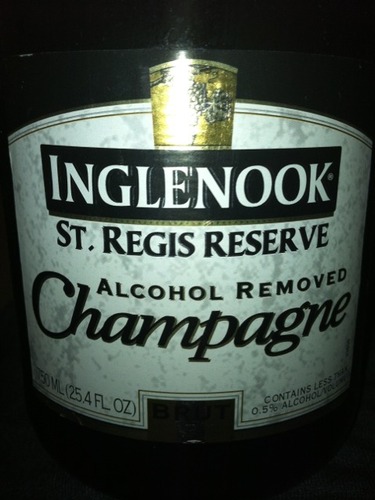

At the Champagne Bureau in Washington, Heitner showed me his Wall of Shame collection of mislabeled Champagne bottles, including one, St. Regis Reserve Alcohol Removed Champagne, that he called “just a nightmare.”

“This isn’t a snobby issue at all,” he said. “It’s a where-your-food-came-from issue.” That’s something Heitner says that a younger generation inherently understands. “We’ve been doing seminars for many years. The people we educate at a culinary school aren’t necessarily going to go out and buy a lot of Champagne. But 15 years down the road, they will.”

The Champagne Bureau is banking on the fact that a younger, more food-and-drink-knowledgeable generation — the one that has resoundingly chosen craft beer over Budweiser — eventually will reject André or Korbel. It’s also betting that this generation won’t embrace lesser-priced sparkling wines such as Italian prosecco or Spanish cava. And that the economy will improve, and that a generation saddled by massive student debt will be able to afford real Champagne.

As Heitner placed the empty bottle of St. Regis Reserve Alcohol Removed Champagne back on his Wall of Shame, he said: “We take a very long view.”

Jason Wilson is the author of “Boozehound” and the winee-book series “Planet of the Grapes.” Follow him on Twitter @boozecolumnist.