The great transatlantic trade charade

Politico | 4 February 2019

The great transatlantic trade charade

By Hans von der Burchard and Adam Behsudi

The United States and Europe say they want to negotiate a trade deal, but the talks look like a smokescreen.

The prime motivation for keeping everybody at the table — even as an act of political theater — is to try to stop U.S. President Donald Trump from imposing a 25 percent tariff on European cars and igniting a full-blown trade war.

When it comes to the hard tacks of negotiations, however, the two sides have seemingly insuperable obstacles, which would seem to kill off the talks even before they have begun.

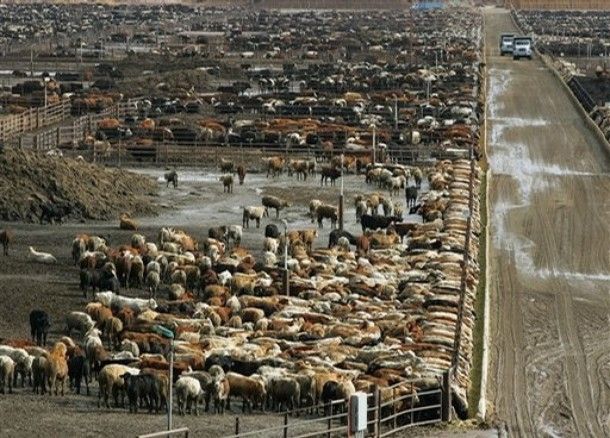

The Americans want to win greater access to EU agricultural markets, but the Europeans want to leave food out of the talks for fear of rekindling the massive popular backlash against a potential Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership over recent years. For its part, Brussels wants to eliminate tariffs on industrial goods, including cars, but the Americans are not keen to do so.

"It’s a bit of a show. I don’t think that these talks can lead to a result," said Bernd Lange, chair of the European Parliament’s trade committee. "All in all, it’s a concept to de-escalate, but you can’t seriously negotiate with it."

Last July, Trump struck a truce with European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker not to impose new tariffs, and the game now seems to preserve the armistice as long as possible.

EU trade chief Cecilia Malmström is seeking to play up positive developments: "We’re advancing, we have made some very important progress there and there’s a process that is positive, I think," she told the World Economic Forum in Davos late last month. At the same time, she reminded Trump that both sides have agreed "that we would not impose tariffs on each other" as long as negotiations continue.

But the difference between the two sides on the objectives means most observers have little hope of real progress. “Both sides put their cards on the table but they seem to be playing different games,” said Peter Chase, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

A U.S. industry official said both sides need to work harder to find common ground or the exercise risks running out of steam. “We’re at a standoff here and I don’t see much political will on either side to break that down,” the official said.

Others have an even more negative assessment, viewing the talks as simply a maneuver by the EU to avoid car duties.

“A win for the EU is anything that excludes them from the tariffs on autos,” said Stephen Claeys, a partner at the law firm Wiley Rein and former trade counsel for the House ways and means committee, one of the primary trade committees in the U.S. Congress. “They’re not being driven by wanting a deal in and of itself, they’re being driven by wanting to avoid those tariffs.”

Soybeans and early harvest

Volker Treier, head of foreign trade at the German Chamber of Commerce, said trade officials in Washington are also trying to show progress in talks to avoid a return to tariff war.

U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has sought to convince Trump that the true battle to "make America great again" lies in a crackdown on China, and that he should join the Europeans against Beijing instead of waging a trade war on two fronts.

"I already visited USTR two months ago and had the impression that they were frantically looking for good arguments to keep up discussions with the EU and to reduce the trade deficit," Treier said, referring to the president’s obsession with America’s negative trade in goods balance vis-à-vis Europe.

"It’s an attempt to offer something [to the president] to avert the other," said Treier, who was in Washington last week to meet with USTR, congressmen and senators.

One of the goodwill gestures that both sides have focused on is soybeans: Last week, the European Commission boosted imports of the American crops by recognizing them for producing subsidized biofuels. Brussels is also seeking to increase imports of U.S. liquefied natural gas.

But a former senior trade official said Brussels “played the U.S. like a fiddle” with such promises. “There’s no tariffs on soybeans in the EU and the EU wants to desperately buy as much American natural gas they can get their hands on,” he added.

The industry official said there is already wide recognition at the top of the Trump administration that the EU’s commitments on soybeans and natural gas are merely “window dressing.”

Brussels and Washington have also suggested accelerating negotiations by pursuing a step-by-step approach, starting with an "early harvest" on regulatory cooperation, an area where they see benefits from removing unnecessary double-testing procedures.

“Progress with the Trump administration is most likely in individual separate projects agreed between the two sides,” Jean-Luc Demarty, director general of the Commission’s trade department, told the European Parliament’s trade committee last month.

Luisa Santos, director for international relations at the BusinessEurope lobby, shared that assessment: "This is probably the very first time that we want to start trade talks with such diverging objectives," she said, while noting that USTR guidelines also said that talks could be pursued "in stages, as appropriate."

"[This] is opening a possibility to start negotiations, and then we will have to see," she said.

Demands and deadlines

Brussels and Washington, however, know that their window of opportunity to make progress is limited. U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross has until February 19 to present his recommendations on imposing car import tariffs to the president. Trump then has 90 days to decide whether to impose the tariffs, which means his timeframe for using the auto duty threat as leverage in negotiations ends in mid-May.

"This is exactly what we have always said we want to avoid: To negotiate with a gun to our head," said EU lawmaker Lange. "First of all, this is completely unrealistic in terms of time. And secondly, I don’t think we should negotiate at all without addressing the issue of threats. The Americans still haven’t lifted their duties on European steel and aluminum. They have imposed tariffs on Spanish olives. How can we seriously negotiate under these circumstances?"

Lange has written a draft parliament resolution, calling on EU countries not to adopt draft Commission mandates for starting trade talks with the U.S.

Adding to Brussels’ grumbles about tariff threats comes the aggressive U.S. push for car quotas. Mexico and Canada have already accepted such a quota, which is anathema to trade officials in Brussels. The EU’s Malmström has said the bloc "wouldn’t" accept such demands.

The EU has yet another fundamental problem when it comes to negotiating with Trump: The president has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement on climate change. The European Parliament last year passed a resolution saying that membership of the Paris Agreement is a prerequisite for trade deals.

In other words, should Brussels and Washington agree on the scope for negotiating a trade deal, it could be torpedoed by the Parliament, which was already highly critical toward TTIP talks with the U.S.

Daniel Caspary, a senior lawmaker from the European People’s Party and a staunch advocate of transatlantic cooperation, said that talks only stand a chance if both sides allow more flexibility.

"The negotiators need room to maneuver. As long as this is not possible, I think it will be extremely difficult to deliver anything during this mandate of the European Commission," which ends in the fall, he said.

"By then, we’re already about to enter the 2020 presidential elections in the U.S., which will make it almost impossible to negotiate a deal and obtain concessions."