TPP strengthens controversial IP arbitration

IP Watchdog | 30 November 2015

TPP strengthens controversial IP arbitration

by Steven Seidenberg

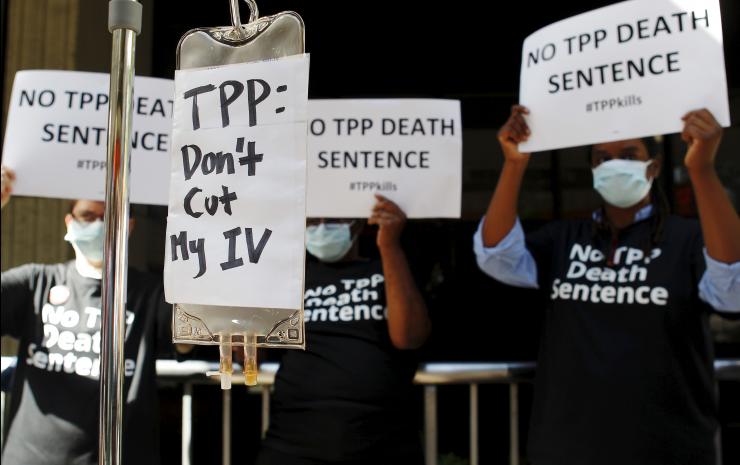

The US government has been less than candid about the Trans-Pacific Partnership. While the agreement was being negotiated, the US Trade Representative stated that a much-criticized arbitration process included in the TPP would not apply to intellectual property. Turns out, it does apply to IP. And it provides foreign corporations with a huge advantage in IP disputes – private arbitrations that can override courts and statutes, effectively rewriting a nation’s IP laws.

The US is the main force behind the TPP, a recently concluded free-trade agreement among 12 nations accounting for 40 percent of world trade. This agreement, which still needs to be ratified by the countries involved, would greatly reduce impediments to trade in goods and services. It also would require all signatory countries to accept a controversial arbitration process known as “Investor-State Dispute Settlement” or ISDS.

ISDS isn’t new. Over the last 30 years, ISDS provisions have been put into more than 3,000 international trade agreements. However, ISDS has changed over time. It originally was intended to protect investors, such as mining companies, whose property was seized by foreign governments without appropriate compensation. ISDS allowed investors to complain to neutral arbitrators, who in turn could order expropriating governments to pay fair compensation.

But in recent years, investors’ lawyers (many of whom also work as ISDS arbitrators) have successfully expanded the scope of ISDS. Arbitrators have issued multimillion dollar awards against countries because ordinary government actions – protecting such things as health, labor rights, and the environment – interfered with foreign companies’ expected profits.

In Metalclad Corp. v. Mexico, for instance, an ISDS panel ordered Mexico to pay $16.2 million to a US company because a Mexican municipality denied the company a permit to expand a toxic waste facility into an environmentally sensitive area. In Ethyl Corp. v. Canada, a US seller of gasoline additive MMT brought an ISDS action when Canada banned MMT because of its health and environmental dangers. After Ethyl won a preliminary ISDS decision, Canada settled the case by paying $13 million, lifting the ban, and advertising that MMT is safe (although Ethyl’s home country, the US, bans the use of MMT in gas).

ISDS and IP Rights

While the TPP was being negotiated in secret, the USTR declared that “IP rights would not be subject to TPP’s ISDS provisions,” said James Love, Director of Knowledge Ecology International. Yet once the treaty’s text was released on 5 November, it was clear that the USTR’s statement was inaccurate. Article 9.1 of TPP’s ISDS Chapter [PDF] explicitly lists “intellectual property rights” as a form of investment protected by the treaty’s ISDS provisions.

A subsequent provision in this ISDS chapter seems, at first glance, to remove the vast majority of IP disputes from ISDS. Article 9.7, paragraph 5 states “This Article shall not apply to … the revocation, limitation or creation of intellectual property rights….”

This carve-out, however, applies to only one of three basic claims recognized by ISDS: that a foreign company’s investment was “either directly or indirectly” expropriated (Article 9.7, paragraph 1). The carve-out does not restrict the other two types of ISDS claims: that a signatory nation discriminated against a foreign investor (Articles 9.4 and 9.5), or that a signatory nation failed to provide the foreign investor with an internationally recognized “minimum standard of treatment” (Article 9.6).

Moreover, the carve-out doesn’t really protect signatory nations against claims that they expropriated IP rights. The carve-out applies only “to the extent that the issuance, revocation, limitation or creation [of IP rights] is consistent with [TPP’s] Chapter 18 (Intellectual Property) and the TRIPS Agreement.” This added language makes it easy for foreign companies to avoid the carve-out, according to many experts.

“Any well pleaded request for ISDS arbitration will contain an argument that the foreign government’s action on IP rights is inconsistent with Chapter 18 or TRIPS – so then the Article 9.7 carve-out does not apply,” explained W. Edward Ramage, a partner in the Nashville, Tennessee office of Baker Donelson.

Such a pleading will get the dispute before arbitrators, who must then rule on the procedural issue of whether the government violated IP protections in TPP or TRIPS. To determine that, arbitrators must rule on the substantive issue of whether the government expropriated IP without due compensation. If such expropriation occurred, that will almost certainly be a violation of TPP and/or TRIPS.

The carve-out, in short, will not procedurally prevent arbitrations from being heard, nor will it substantively restrict expropriation claims. It is “toothless,” said Ramage.

IP Law under Attack

TPP would thus allow foreign companies to bring a wide range of challenges to government IP rulings. A foreign business could challenge the denial of a patent application, a ruling that it infringed a trademark, a decision that its own copyrights weren’t infringed, or a statute restricting the scope of patentable inventions. Any government action that adversely affects a foreign company’s IP expectations could be attacked.

Such ISDS challenges are already being brought under other free trade agreements, none of which list IP as a protected investment. Eli Lilly, for instance, has brought an ISDS proceeding against Canada, because Canadian courts struck down patents on two profitable Lilly drugs. Philip Morris has brought ISDS proceedings against Australia and Uruguay, alleging that the tobacco giant’s trademark rights (and cigarette sales) have been harmed by the countries’ requirements that cigarettes be sold in plain packaging.

But TPP, according to some experts, will increase the range of government IP actions that can be challenged under ISDS. That’s because the “TPP includes a new footnote, not previously released as part of any other [free trade agreement’s] investment chapter,” Prof. Sean Flynn of American University Law School wrote in a blog post. This footnote is found in TPP Article 9.7, paragraph 5, which, ironically, creates the IP carve-out that supposedly limits expropriation claims. The note states that expropriation claims can be used to challenge “exceptions” to IP rights.

“This expands the range of challenges that can be brought by companies,” Flynn wrote. It makes clear “that private companies are empowered by the treaty to challenge … exceptions like the US fair use doctrine, or individual applications of it.”

This expansion of expropriation claims is likely to hit the US harder than any other TPP country. “The US has the biggest copyright exception: fair use. That is begging to be challenged under TPP,” said Love.

Custom-Made Justice

Once an ISDS challenge is brought, there is almost no check on the power of the unelected panel of private ISDS arbitrators. The arbitrators are not required to follow any precedents, and there are no substantive appeals from their rulings. As a result, ISDS arbitrators can ignore statutes, regulations, even IP decisions from a nation’s highest court, and make rulings based purely on their own notions of what constitutes expropriation or a required “minimum standard of treatment.”

“ISDS could become a form of supra-judicial review,” said Ramage. “If a company doesn’t like a final court or administrative agency decision in a matter, it can file an ISDS action, claiming that the state action has harmed it or expropriated its property. A country’s supreme court no longer will no longer be the ‘court of last resort’ if you’re a foreign investor … instead, it just may be an ISDS tribunal.”

Many governments are already nervous of adverse ISDS rulings. Because just one ruling can force a government to pay hundreds of millions of dollars, plus encourage similar arbitration claims from other foreign investors. It can effectively make a law or policy too expensive to maintain.

This is bad news for IP law in the TPP area. Because of TPP’s ISDS provisions, nations that sign onto the agreement risk the prospect of either paying hundreds of millions of dollars to keep their IP laws in force, or amending their IP laws to satisfy disgruntled foreign businesses.

TPP’s provisions on IP and ISDS will “upset the international intellectual property legal system,” Flynn wrote. There are good reasons for his concern.

The USTR was repeatedly asked to comment on the issues raised in this article. The agency provided no response.