Trade deals a closely held secret, shared by more than 500 advisers

Washington Post | 18 February 2014

Trade deals a closely held secret, shared by more than 500 advisers

By Howard Schneider

The details of the Obama administration’s proposals for a massive 12-nation trade zone in the Asia-Pacific region are off limits to most Americans, held close by negotiators who worry that too much openness would make it impossible to reach a deal.

But a chosen few have been allowed to peek behind the curtain and share some of the most sensitive documents.

Who are they?

Richard Douglas, a vice president at General Electric, a company that has shifted extensive production overseas.

David Chavern, a vice president at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a chief advocate of the free-trade agreements.

Craig Kramer, a vice president at medical giant Johnson & Johnson, part of an industry with deep interests in global intellectual property rules and other aspects of the negotiations.

Robert Roche, chairman of a marketing company that is headquartered in China and a significant donor to the Obama campaign.

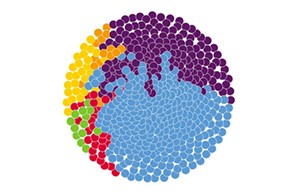

In what has been criticized as an industry-dominated advisory system, those executives are among more than 500 people who are allowed to read and comment on the negotiating proposals that the United States presents to its trading partners. They can look at the material on a secure Web site, comment on trade policy proposals in regular meetings, and request one-on-one sessions with negotiators — favored access that gives them a direct pipeline into the talks.

The access isn’t exclusive to industry. The heads of the United Steelworkers, Teamsters, United Auto Workers and the United Food and Commercial Workers unions sit with top corporate executives on the same presidentially appointed trade panel — the top “tier” of a an advisory system that includes around two-dozen committees.

Diverse small industries, including local farm bureaus and the International Association of Skateboarding Companies, have also been represented. And membership comes with limits, including security clearances and a non-disclosure agreement that carries criminal penalties for violators.

But as the impact of globalization becomes more contentious during the slow economic recovery, more voices are demanding to get involved. That’s because the debate over trade agreements isn’t just about tariffs anymore. It’s about how far the United States should go in insisting that its trading partners put stronger labor and environmental standards in place, how technically complex industries such as biopharmaceuticals should be regulated, and what standards should govern emerging technologies such as cloud computing.

Partly in response to criticism, U.S. Trade Representative Mike Froman recently announced plans to add more labor and public interest representatives to the committees, and set up a new panel dedicated to “public interest” groups.

“The door is open and we are interested in further diversifying,” Froman said in a speech last week.

The stakes have risen as the administration advanced negotiations on the Transpacific Partnership (TPP), a proposed 12-nation pact that includes nations such as Japan, where the United States hopes to export more, and Vietnam, which wants to attract more manufacturing investment. Core Democratic groups and members of Congress have argued that the structure of the advisory system has put private business in a stronger position to shape U.S. proposals that could make it easier for companies to relocate to countries within the new trade bloc, or subject U.S. environmental and other regulations to the decisions of an international investment court.

Froman has tried to allay those fears, arguing that U.S. businesses and workers will gain more from opening markets under the agreement than they might lose through stiffer import competition. The process has not been closed more than necessary, he said, because public hearings held alongside some of the negotiating sessions have given hundreds of public groups, citizens and others a chance to have their say.

Still, the process has left a sour taste for many, including important Democratic lawmakers such as Rep. Sander M. Levin (Mich), who has said that there should be a broad public debate about trade and more oversight of the details of the TPP talks.

Panel members “get face time [with top officials] . . . You can see them in intimate meetings, and that has value for anyone,” said Durwood Zaelke, head of the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development and a member of the Trade and Environment Policy Advisory Committee.

“But there is a limit,” he said. “You do not sit and make policy for the U.S. trade representative, and you do not counterbalance the strong industry presence.”

The advisory system was established in the 1970s to give the private sector a more formal role in setting trade policy and shaping negotiations.

Members of the committees — corporate and non-governmental groups — say that the system does allow substantial input.

“It does contribute not only to democratization but to the substantive quality and integrity of the process,” said Jennifer Haverkamp, the former head of USTR’s environment office and, subsequently, a member of one of the advisory committees representing environmental activists.

And even if private business dominates the membership, their interests are not monolithic. Different branches of the same industry may conflict — textile companies that have fully outsourced their manufacturing argue for lower import tariffs, for example, while those with domestic plants argue to keep them.

A treaty as broad as the proposed Transpacific Partnership inevitably involves tradeoffs between industries that are expanding, and likely to favor more openness, and those whose influence is waning and are concerned about stiffer competition from imports.

Are sugar subsidies, for example, worth maintaining if they could be swapped for regulations favorable to the telecommunications industry?

“Multiple opinions are expressed, and the trade negotiators take that into account,” said David Gaugh, vice president of the Generic Pharmaceutical Association, and, until his term expired in mid-February, a member of the industry panel on pharmaceuticals.

The rules for licensing generic versions of the most advanced medicines are part of the TPP discussion, and an area where the interests of brand-name companies, which want to keep longer periods of patent protection, contradict those of generic manufacturers.

The terms for many of the advisory committee members expired in February, and a notice published in the Federal Register this week promised wider opportunities for representatives of unions and non-governmental organizations.

Union representatives have long argued that, along with the panel dedicated to labor issues, they should sit on the industry committees where representatives from the auto, aerospace, pharmaceutical and other businesses dig deep into the weeds of the trade rules that affect them most.

Union representatives said they will urge interested members to dust off their résumés.

“This not a cure-all for all of our complaints about trade. . . . It is still officially behind closed doors,” said Celeste Drake, a trade policy specialist with the AFL-CIO. “But it will be very helpful.”

Washington Post staff write Dan Keating contributed to this report.