How does China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ match up against the TPP ?

South China Morning Post | 24 January 2017

How does China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ match up against the TPP ?

by Frank Tang

US President Donald Trump signed an executive order on Monday to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade deal signed by 12 Pacific Rim countries, putting an end to a plan to introduce stricter and “fairer” rules for global trade in the region.

So, will Chinese President Xi Jinping’s brainchild, the “One Belt, One Road” programme, prove a better idea for forging closer trade and investment ties and creating common prosperity ?

Here are a few key differences between Xi’s strategy and the trade deal that Trump disliked.

1. Purpose

The negotiations for the TPP date back to 2005 when the Doha round of trade talks led by the World Trade Organisation stalled and later failed. The TPP was a cornerstone for the Obama administration’s plan to revive trade and implement higher standards for trading rules in the Pacific region. The US also proposed the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, a broadly similar agreement with the European Union.

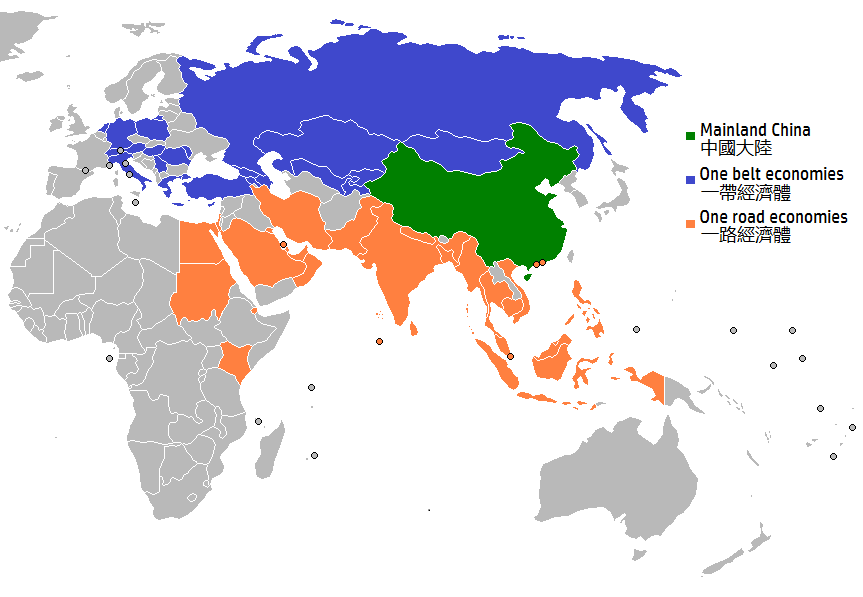

The One Belt, One Road initiative was launched by Beijing to promote trade and investment along old trade routes. Beijing is trying to export its surplus products and manufacturing capacity plus influence over 60 countries through the strategy.

2. Membership

China is not included into the TPP and the US plays no role in One Belt, One Road.

Twelve Pacific Rim member countries originally signed up for the TPP. They include key developed economies such as Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and Singapore, plus selected emerging countries including Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru and Vietnam.

The One Belt, One Road initiative now covers more than 60 countries in Asia, Africa and Europe. The vast majority, however, are developing countries in dire need of money and aid from China.

The number of members is expected to rise as it is an open initiative with no entry barriers.

3. Institutions

TPP is an intergovernmental trade deal. The US joined negotiations after Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore signed the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement, the predecessor of the TPP, in 2005. But it has since dominated the initiative, given the size of its economy, market and the international pre-eminence of the dollar.

The talks involved a lot of give and take even among allies such as US and Japan. For Trump, the trade pact will only increase the risk of jobs leaving the US for cheaper manufacturing bases overseas.

China is throwing a lot of institutional support behind its One Belt, One Road initiative, including creating the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Silk Road Fund, to ease deals.

4. Rules

The rules governing the TPP are far more comprehensive and stricter than standards set within the World Trade Organisation. Beyond wide cuts in tariffs, the agreement sets new regulations to govern online commerce, the treatment of foreign investors, stricter intellectual property protection, tighter labour laws and an agreement for neutrality regarding state-owned enterprises.

For example, it prohibits exploitative child labour and forced labour, guarantees the right to collective bargaining and prohibits employment discrimination. It also criminalises bribery of government officials and takes actions to reduce conflicts of interest.

China’s One Belt, One Road initiative is based upon projects, not rules. China has made connectivity and infrastructure as the top priorities. Many projects such as rail links have been arranged through negotiations with other nations and are usually funded with Chinese money.