Five reasons why TPP countries should unite to oppose the US pharmaceutical IP agenda

Intellectual Property Watch | 18 August 2015

Five reasons why TPP countries should unite to oppose the US pharmaceutical IP agenda

Deborah Gleeson and Ruth Lopert

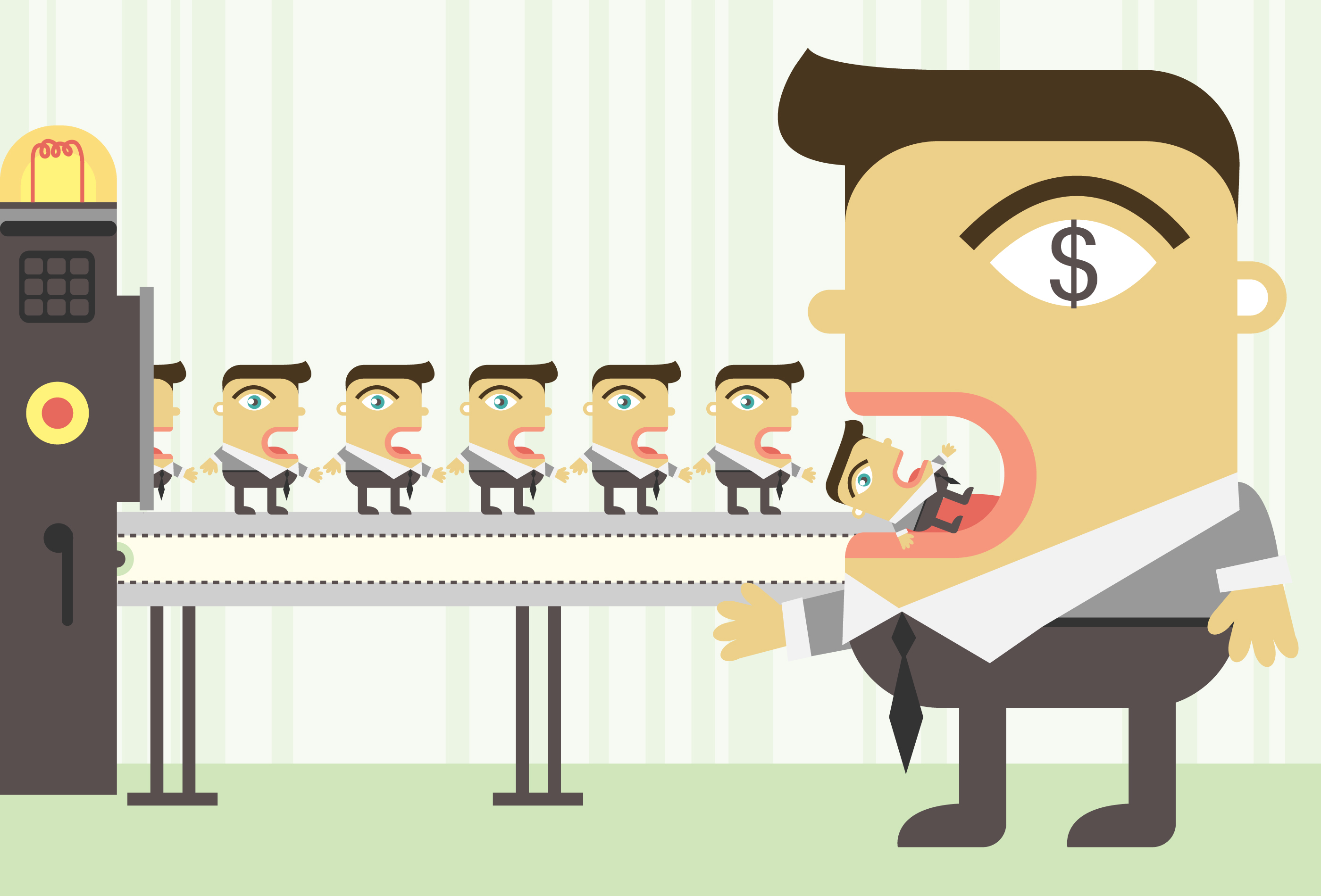

Failure to reach agreement over expanded intellectual property (IP) protections for medicines has proven to be a stumbling block to completion of the 12-country Trans Pacific Partnership negotiations. As expected, the US is continuing to pressure negotiating partners to adopt broader and longer monopoly protections for medicines. But the risks for their health systems are very high – and will be much higher if they don’t stick together in rejecting the US demands.

A leaked draft of the agreement’s IP chapter from May 2014 showed that, with the exception of Japan, the other countries had been consistent in rejecting the US proposals. But more recently, another leaked draft dated 11 May 2015 and published by Knowledge Ecology International last week demonstrated a splintering of this opposition. Rather than pushing back collectively, individual countries appear to be attempting to craft creative language and qualifying footnotes to give the appearance of conceding to US demands while preserving existing standards where possible.

One could be forgiven for thinking that this might seem like a reasonable outcome. But there are at least five good reasons why this is a risky approach – and why pushing back collectively through the final stages of negotiations would be a wiser strategy.

1) The US demands are inherently unreasonable. It is widely recognised that the US is seeking monopoly protections that will frustrate and delay access to affordable medicines in countries that are party to the agreement – and due to spillover effects, potentially to others that are not. As the humanitarian organisation Mèdecins sans Frontiéres has warned: “Unless damaging provisions are removed before negotiations are finalised, the TPP agreement is on track to become the most harmful trade pact ever for access to medicines in developing countries.” President Obama has faced intense criticism even from within his own party for resiling from the 2007 bipartisan May 10 agreement to allow developing countries to apply certain IP flexibilities in the interests of public health.

There is no sensible reason for any other country to accede to the US demands. In Australia expanding and prolonging monopolies on new medicines – in effect, state-sponsored evergreening – will mean further calls on taxpayer funds, or higher patient co-payments, or both. But above all, no credible evidence has ever been presented to justify why the biopharmaceutical industry requires higher standards of IP protection. Development pipelines are full (except of course, for neglected diseases), profits are arguably excessive, and even President Obama has been arguing for a reduction – not an increase – in the duration of market monopolies for expensive biologics.

2) Bargaining with the US is risky business. Under pressure from the US, and anxious to secure gains in market access in exchange for apparent concessions on medicines, negotiators seem to be pursuing solutions in creative wording. But they can’t be sure that ‘carve-outs’ buried in footnotes and fine print appearing to preserve existing policy settings will be interpreted in the anticipated way in any disputes that arise. No country can be confident that even the most carefully crafted workaround won’t end in tears in a trade tribunal and a set of cross-retaliatory measures.

3) Adopting prescriptive obligations in a trade agreement constrains future policy options, even if creative wording averts substantive changes. Tight specification of IP obligations locks countries into existing regimes and prevents the kinds of reforms recommended by the former Australian Government’s Review of Pharmaceutical Patents – such as winding back patent term extensions or reducing effective patent life.

4) The obligations in the TPP will become the template for the next trade agreement. What countries accept – or appear to have accepted, footnotes and exemptions notwithstanding – will then form part of the standard template for the next trade agreement negotiated by the US. Measures included in the text will become the floor for any subsequent agreements, setting new global standards of IP protection that far exceed those required under the World Trade Organization’s TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) Agreement.

5) Developing countries will undoubtedly get the raw end of the deal. Vietnam, as the lowest income country, is likely to be worst affected. While the TPP parties have agreed to a transition period for developing countries, it does not cover all of the pharmaceutical obligations. In the latest leaked draft, earlier proposals for a transition period based on development indicators seem to have been abandoned in favour of a time-based transition: Vietnam will have to graduate to the “higher standard” within a fixed period of time regardless of its rate of development.

The ambition of the TPP countries is that more countries will join once the Agreement is finalised. But countries that sign up after the conclusion of the negotiations will be required to accept whatever the initial 12 have agreed – without any opportunity to creatively ‘tweak’ the text or carve out protections for their own populations.

The bottom line? Acceding to US demands on intellectual property – or even simply appearing to – as a trade off for greater market access for agricultural products and manufactured goods is at best a Faustian bargain. In the interests of global health and access to medicines, the TPP countries should rely on the power of collective bargaining, and rather than allowing themselves to be picked off one by one, stand shoulder to shoulder and reject the US demands outright.