EU-Mercosur trade deal will intensify the climate crisis from agriculture

Todas las versiones de este artículo: [English] [Español] [français] [Português]

GRAIN | 25 November 2019

EU-Mercosur trade deal will intensify the climate crisis from agriculture

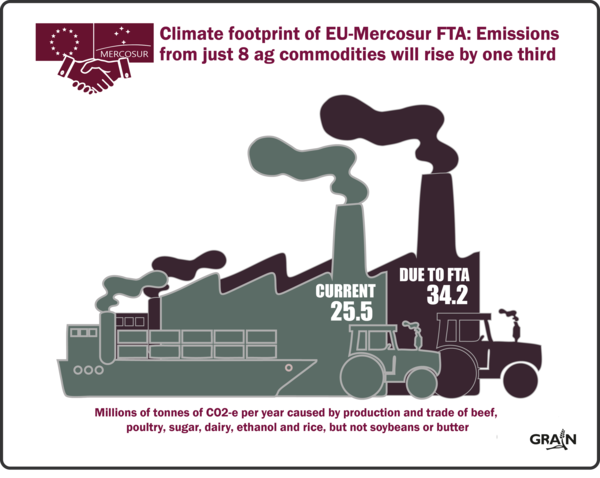

- Emissions from increased bilateral trade in eight key farm products are expected to go up by one-third (34%).

- Beef exports from Mercosur to the EU will be the biggest source of new emissions (82%).

- The EU’s climate footprint from food exports to Mercosur may rise five-fold.

The images of fires raging across the Amazon in August 2019 opened peoples’ eyes around the world to the connection between agribusiness and the climate crisis. The forest was being burned to make way for the production of beef, soybeans and other agricultural commodities to increase the profits of transnational food corporations. An important driver of this devastation is trade. Now, a new trade agreement threatens to further ramp up agribusiness expansion in Brazil, with serious consequences for the climate.

Just two months before the fires captured global attention, the European Union and the Mercosur group of countries – Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay – proudly announced that a new free trade agreement (FTA) has been reached after 20 years of talks. The deal was touted as a 21st century pact that would push member countries towards higher environmental standards, including strong limits on logging and deforestation. The EU even boasted that Brazil’s new president Jair Bolsonaro reneged on his campaign promise to withdraw from the Paris climate accord in order to secure this trade deal.

The EU-Mercosur FTA’s carbon footprint

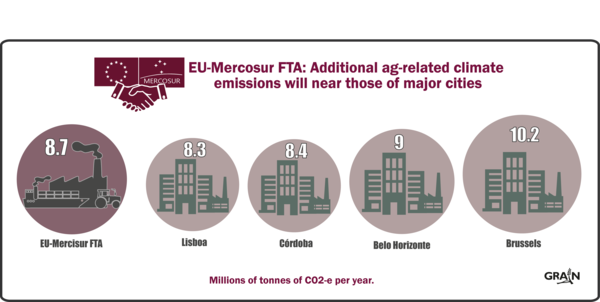

The reality is that the EU-Mercosur FTA will cause a serious increase in global greenhouse gas emissions. While to our knowledge no full audit of the deal’s climate impact has been released, GRAIN assessed the emissions from the agriculture sector by analysing provisions in the deal setting quantitative targets for increased trade in several key farm products. We estimate that these commitments alone will generate nearly 9 million tonnes of additional greenhouse gas emissions per year. This is almost as much as the total annual emissions of the Brazilian city of Belo Horizonte, with a population of 3.9 million.

The new EU-Mercosur FTA has been described as a deal in which Europe gets to sell more cars and cheese to Latin America, while Mercosur countries get to sell more beef and ethanol to Europe. While the increased production and export of cars and other goods and services will clearly contribute to climate disruption, our analysis focuses only on agriculture, a central component of the deal. We looked at the market offers for several high-greenhouse-gas-emitting agricultural goods. These market offers amount to what governments on both sides of the Atlantic promised their farmers and agribusiness lobbies when negotiating the deal. Whether these promises are realised, or even surpassed, remains to be seen.

The commodities we measured the impacts of are: beef, cheese, ethanol (from sugarcane), infant formula, poultry, rice, skim milk powder and sugar. Butter and soybean products were left out of the calculations because, while their tariffs will drop significantly under the deal, no quotas were set. In other words, production and trade of these products will likely grow as a result of the deal, but we cannot say by how much. Our figures would be higher if they were included, since soybeans in particular are a huge source of climate emissions.

We calculate that the direct impact of the FTA will be a rise in greenhouse gas emissions from these eight farm products of 8.7 million tonnes per year (see Annex). That’s more than the city of Lisbon, Portugal, or Córdoba, Argentina, and slightly less than Brussels. Put another way, it’s equivalent to nearly a week’s worth of emissions produced by Royal Dutch Shell, a company responsible for 3% of the entire planet’s energy. Compared to the current level of emissions from trade in these products between the EU and Mercosur, the growth in emissions will be 34%. This is an astonishing increase for governments that, at least in Europe, claim to be climate champions.

How did we reach these figures?

The growth in trade was calculated by comparing the new quotas to old quotas (or to current levels of trade where no old quotas exist) once the FTA’s transition periods are completed. For the growth in emissions, we assumed that the increased trade will be met by increased production. The emissions themselves were calculated for current levels of trade and compared to those of the new quotas using the United Nation’s GLEAM methodology. This includes all emissions from the production of livestock, feed grains and associated farm inputs, meat processing and refrigeration, and transport up to, but not including, point of retail (retail and post-retail emissions from in-home preparation, food waste, etc. were not included).

The top climate-impacting farm products are beef, poultry and ethanol from Mercosur and cheese from Europe. Two-thirds of the new emissions will be produced on the farm, including from fertiliser and manure, while nearly 30% will come from land use changes, including deforestation. And while much of the incentive to increase production and trade will come from quotas and tariffs, the FTA also imposes rules on geographical indications, which will create new market rights in Latin America for European cheese producers. Finally, it’s worth noting that while Mercosur will generate the bulk of these new emissions, the emissions from the growth of EU dairy exports to Mercosur will rise by a whopping 497%.

Other environmental, social and economic impacts

In addition to worsening the climate crisis, the agriculture provisions of the EU-Mercosur FTA carry other threats. For example, according the French sugar industry, 74% of the pesticides used in Brazil’s sugar cane farms are banned in Europe, and Brazil has just approved a genetically modified sugar cane variety that is banned in Europe. The government of Brazil also allows the use of glyphosate before harvest to speed up ripening, when many European cities and countries are struggling to get glyphosate banned. This means that unwanted GMOs and agrichemicals are likely to enter the EU under the cover of this agreement.

Further, the deal expands markets for agribusiness commodities while doing nothing to support small farmers or food production. Indeed, the market openings for exports from Latin America are expected to result in increased pressure on indigenous and peasant communities who being driven from their lands. Another result may be heightened disputes over water due to demand for irrigation and cattle raising, and even more deforestation and loss of biodiversity. In Europe, this trade agreement will also promote the interests of agribusiness while further undermining small farmers, rural communities and sustainable agriculture. In a region where investments and economic development promoted by FTAs are only captured by large companies, the EU-Mercosur deal is expected to fire up the race to the bottom in producers’ prices, deepening the debt and bankruptcy already pounding Europe’s rural areas.

The trade deal also masks a serious contradiction. The EU’s increased ethanol imports through the FTA are expected to be used to meet Europe’s “green” transport fuel targets. The same may happen with the increased EU imports of cheaper soy products, which could become attractive feedstock for Europe’s biodiesel industry. According to the organisation Transport & Environment, this could lead to further deforestation and land grabbing in countries like Brazil. EU governments could end up causing more climate destruction abroad in order to meet their climate targets at home.

Fight FTAs to save the climate

Trade deals are powerful drivers in expanding the industrial food system, which the International Panel on Climate Change says is responsible for up to 37% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Lobbyists for the different sectors involved, from seeds to supermarkets, have been pushing governments to sign and implement these pacts since decades. They give agri-food companies and the farmers who supply them greater market reach and investment rights – a chance to capture more profits. In turn, the spread of the industrial food system creates enormous pressure on our climate.

With the food system being such an important contributor to the climate crisis, business as usual is simply not an option. Unfortunately, new trade deals reflect old thinking—precisely the kind of thinking that created the crisis in the first place. The EU-Mercosur FTA is not an isolated case. Industrial agriculture is also central to the US-China trade talks, which Trump says will double US farm exports to China. And the upcoming EU-Australia-New Zealand deal will likely boost European imports of beef and dairy with higher CO2 emissions intensities.

If we are serious about cutting greenhouse gas emissions, we have to take action on key global mechanisms that promote the expansion of industrial food and agriculture—with trade agreements at the top of the list. The CEOs of companies like Danone and JBS are aware of the challenge, as their very business models – which produce these climate emissions and rely on this trade system – are on the line.16 But "stewardship" will not come from compensating for the destruction, as these companies advocate. It must come from giving way to community-controlled, local food systems. That means handing resources and the reins over to small scale producers, regional processors, short circuits and local markets. For that to succeed, we urgently need to stop new trade deals like EU-Mercosur.