A free trade agreement for the worse

The Edge Markets - 29 June 2019

A free trade agreement for the worse

By Jomo Kwame Sundaram and Nazran Zhafri Ahmad Johari

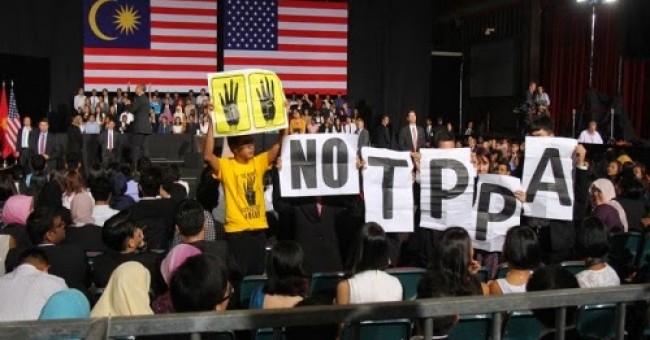

There is considerable concern about the government’s possible ratification of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the successor to the TPP after US President Donald Trump’s withdrawal following his inauguration in late January 2017.

Although free trade is attractive, especially to consumers desiring lower import prices, it is generally acknowledged that no country has ever developed without policy interventions, typically involving trade, to develop new economic capacities and capabilities.

Thus far, the CPTPP has been ratified by 7 out of 11 signatory countries, with Malaysia one of the four outliers. Ratification advocates wishfully claim that the CPTPP would boost Malaysia’s economic growth by greatly increasing exports.

They cite much-disputed Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) and World Bank studies, by the same authors, using a dubious methodology even rejected by the US government’s International Trade Council in mid-2016 — under President Barack Obama. The reports cite increased exports, but are silent about the far greater increase in imports.

Dubious gains from trade

Trade economist Rashmi Banga’s CPTPP: Implications for Malaysia’s Merchandise Trade Balance for the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development is the only available study of its likely economic impact on the country. Her detailed and nuanced analysis suggests much need for caution.

While exports to CPTPP countries will rise 0.2%, imports will grow 6.0%, setting Malaysia’s annual merchandise trade balance back by US$2.4 billion, or about RM10 billion. This would worsen its balance of payments as its services trade balance has always been in deficit.

The original TPP promised Malaysia more exports, mainly to the US, although such claims were grossly exaggerated by the PIIE. Without the US, the paltry gains have diminished further. As Malaysia already has free trade agreements (FTAs) with other major trading partners in the CPTPP, such as Japan, Australia and Singapore, participation in the agreement has little to offer.

The two largest imported items are cars and plastic materials. Banga estimates that imports of vehicles, mainly from Japan, will rise 36% if customs duties come down to zero. This is likely to wreak havoc on Malaysia’s already vulnerable automotive industry.

The CPTPP will also enable much more imports of plastic materials, including waste and scrap, by around 35%, mainly from Japan, Singapore and Australia. Over a quarter century ago, then World Bank vice-president Larry Summers infamously suggested that toxic waste might be dumped in poor countries in Africa owing to the lower opportunity costs involved. On the cusp of becoming a high-income nation, the last administration belatedly took the advice by licensing ostensible plastic waste recycling plants.

Malaysian FTAs with Singapore, Japan and Australia affect 82% of its CPTPP exports and 84% of imports. Hence, Malaysia will not lose much to trade diversion by not ratifying the CPTPP — about US$53.2 million, or 0.09% of current exports to other CPTPP countries. On the other hand, it will retain revenue from its relatively higher import tariffs.

21st-century gold standard?

CPTPP advocates claim that Malaysia will also gain the respect of the international community by ratifying its new “cutting-edge”, “state-of-the-art”, “gold-standard”, “21st-century FTA”. In fact, the CPTPP will mainly benefit transnational firms at the expense of consumers, workers and the public in participating economies.

With the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) provisions, for example, foreign investors will be able to sue the government for loss of revenue and profits if government policies are changed, or if contracts are renegotiated, even if it is in the interest of the public like banning toxic or carcinogenic chemicals.

ISDS involves binding “private” arbitration, bypassing the national judicial systems. This significantly strengthens the rights of foreign investors at the expense of those of governments with typically more modest means to litigate cases, thus exercising a “chilling effect” on governments to comply with foreign corporate demands. Government ability to improve public policy will thus be restricted.

Ironically, the Trump administration is now opposed to ISDS. TransCanada sued the US government, under the ISDS provisions of the North American Free Trade Agreement, for US$15 billion after the Obama administration cancelled its Keystone XL pipeline project. The case was dropped after Trump revived the project.

CPTPP proponents insist that strengthening intellectual property laws will benefit everyone as it will incentivise research and innovation, a claim for which there is no evidence. The TPP agreement would have lengthened monopolies on patented medicines, kept cheaper generics off the market and allowed natural biological materials and processes to be patented.

The Penang-based Third World Network has long highlighted many such CPTPP dangers, for instance, citing the Malaysian government’s procurement of an Egyptian generic treatment of Hepatitis C — estimated to afflict almost half a million Malaysians — for RM1,300, instead of the patented US treatment costing almost RM300,000.

Encircling China

The TPP was originally a minor plurilateral regional trade agreement involving four countries. The Obama administration decided to use it to check China’s growing economic influence.

With the recent escalation of tensions

between China and the US, many Malaysians are understandably concerned about how the growing economic conflict will affect economic prospects. Ratifying the CPTPP is likely to be seen as taking sides, even without the US in it.

To secure broad public support in the face of growing scepticism about the benefits of trade liberalisation associated with globalisation, the Obama administration involved over 700 advisers, mainly representing corporate interests, in the drafting of the 6,350-page TPP.

Ironically, the US is no longer party to an agreement largely drafted by US corporate interests. A few of the most onerous clauses of the TPP have been suspended in the CPTPP, but if Japan, Australia and Singapore succeed in bringing the US back in, the White House will insist on their re-inclusion.

Withdrawing from the CPTPP would send a clear message that the new Malaysian government is determined to put the needs of its people over the interests of powerful transnational corporations. In any case, there is no requirement, obligation or deadline for any signatory government to ratify the CPTPP.