With no major trade deals signed in recent years, India turning an outlier

The New Indian Express - 01 March 2020

With no major trade deals signed in recent years, India turning an outlier

By Jayanta Roy Chowdhury

When news broke that US President Donald Trump would not be accompanied by his trade representative Robert E Lighthizer, it became quite clear that India and the US would not be able to broker even the preliminary trade deal they had so wanted.

It also underlined that India has become an outlier of sorts in trade negotiations by failing to strike even a single major deal in recent years.

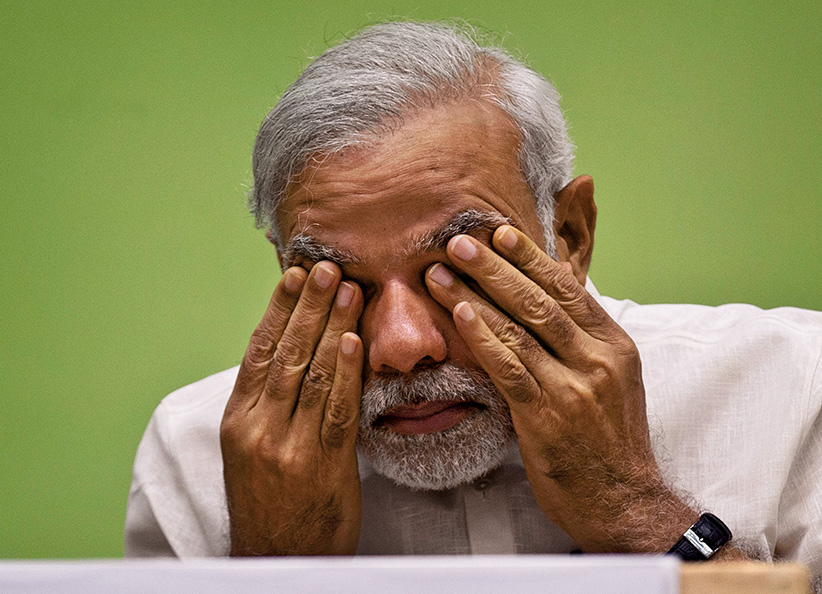

Talks to be a founder member of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) — the world’s largest trading bloc that includes China, ASEAN, Japan, Korea, Australia and New Zealand — fell through last year when Prime Minister Narendra Modi walked out on the deal at the last moment.

An off-again-on-again free trade pact with the European Union still lies in the doldrums, while smaller trade pacts with Australia and New Zealand and even BIMSTEC (Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation) — the regional grouping India created to counter Pakistan — also lie in limbo.

The feeling now in global trade negotiating circles is that India is a recalcitrant partner, difficult to negotiate with.

“India will bring in points for discussions after negotiations on those points have already been concluded, and that too at the last moment, making it impossible to come to a decision within a given time frame,” said a Malaysian diplomat involved with the RCEP negotiations.

Diplomats say Indian officials wanted an auto-trigger mechanism that would allow them to charge higher import duties if it finds there is an unexplained surge in import of a product after negotiations on tariff issues were already concluded.

In other instances, Indian trade negotiators seem to have slept on the job by agreeing to cut tariff and then waking up to the fact that the cuts could hit India hard after the industry lobbied against them.

One Indian trade negotiator said that in some of the negotiations, comprehensive position papers were not ready when India went in to discuss a deal.

Ideally, trade negotiators talk to all constituencies back home before coming up with a list of what they would like to get from a deal: a list of ‘holy cows’ or industries they must protect to save jobs and other interests, and a list of what they can give up in the bargaining that must follow.

In India’s case, this transactional approach sometimes came rather late in the day, after being prompted by various lobbies.

In negotiations with the US, India almost agreed to open up to US poultry imports before last-minute frantic appeals by Indian poultry farmers scuttled the move.

However, labouring certain points has also meant India has not been able to strike deals. Indian dairy industry wants to keep US dairy products out of the market and Indian negotiators have toed the line, by citing the fact that Indians preferred milk from cows fed on the vegetable fare and American bovines were fed non-vegetarian feed.

The protectionist attitude among Indian bureaucracy was so strong that compromise solutions such as making compulsory consumer labels that indicate the diet of dairy animals were also rejected, forcing US dairy industry to recommend to the Trump Administration to take away India’s GSP benefits that gave more than 2,000 Indian product lines duty-free access to the American market.

Influential lobbyists in India have also meant that certain parts of a deal could not be sewn up even though it would hardly hit the Indian economy.

Wines are an example of it. India’s wine-makers, whose total turnover is minuscule, have scuttled all bids to open up the wine trade by reducing one of the highest tariff rates in the world, an important demand for the Europeans and Americans.